Art and Music at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In parallel with the BSO’s “Music for the Senses” programming, Boston’s MFA (visit the museum at 465 Huntington Ave) compiled images related to music or sharing inspiration with the pieces being performed.

John Singer Sargent, Prometheus, 1921. Oil on canvas. In 1916, John Singer Sargent was asked to provide murals for the newly built Museum of Fine Arts. He welcomed the opportunity, for in his mind, mural painting was a more significant art form than either landscape or portraiture and, therefore, was a surer road to artistic immortality. Decorating the Museum also guaranteed that his work would be on permanent display near the masterpieces of ancient and old-master art he so admired. To complement the grand, neoclassical style of the building, Sargent depicted stories from the classical past and also devised new themes, such as a debate between Classic and Romantic Art, enacted by characters from Greek mythology. While the images tell no single story, many pay tribute to the Museum’s role as the guardian of the arts. The Prometheus myth has inspired countless works, including Franz Liszt's Prometheus, Symphonic Poem No. 5, and Alexander Scriabin's Prometheus, Poem of Fire, both on the BSO's "Music for the Senses" program of April 4-6, 2024. (Bartlett Collection-Museum purchase with funds from the Francis Bartlett Donation of 1912 and Picture Fund / Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

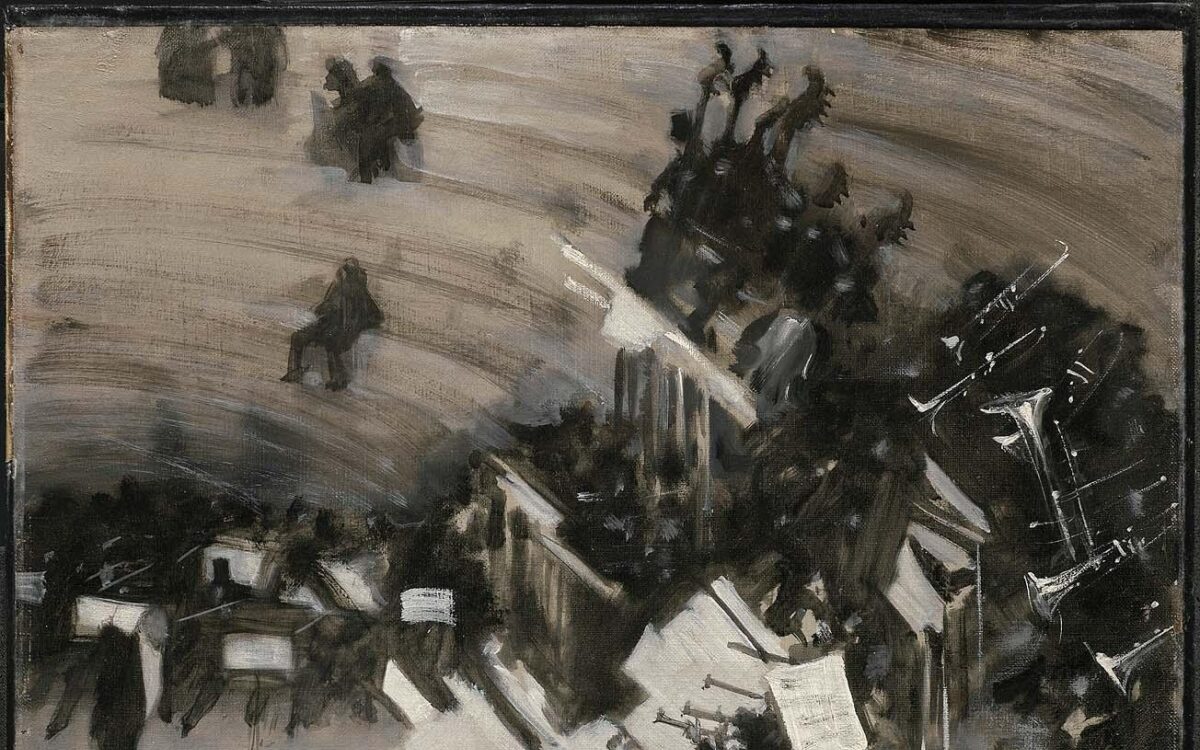

John Singer Sargent, Rehearsal of the Pasdeloup Orchestra at the Cirque d’Hiver, ca. 1879-80. Oil on canvas. Jules Étienne Pasdeloup conducted an orchestra in Paris from 1861 to 1887 and championed modern composers such as Richard Wagner and Gabriel Fauré. He rehearsed at the Cirque d’Hiver, a building used for indoor entertainments like the circus. John Singer Sargent, an ardent amateur musician, frequently attended the concerts and painted them several times. This picture is his most abstract treatment of the subject and represents one of his boldest experimentations with Impressionism. The monochrome palette, seemingly quick execution, and energetic composition suggest both the dance of musical notes across a page and the vital sound of the music itself. (The Hayden Collection-Charles Henry Hayden Fund / Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

"

data-credit=""

alt="The Jackson Pollock painting "Troubled Queen""

/>

"

data-credit=""

alt="The Jackson Pollock painting "Troubled Queen""

/>

Shiva as Lord of Music (Shiva Vinadhara), 900 - 970 A.D. Green schist. Shiva sits cross-legged with his torso swaying to one side. He has four arms, of which two are missing at the elbows. The missing lower hands would have held the god’s vina (stringed instrument); the sounding gourd of the instrument appears over the god’s left shoulder. The upper right hand holds a skull-topped scepter and his upper left hand, a drum. This sculpture belongs to an important group of sculptures from a 10th-century goddess temple near the city of Kanchipuram. It’s one of only four male figures to survive from the temple. Here we see both Shiva’s terror-inspiring features (his skull-topped staff) and attributes of his benevolence: he wears the jewels and pearls of a king and sways to the music of the stringed vina he once held. (Maria Antoinette Evans Fund / Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Bhudevi, late 11th-early 12th century. Bronze. This bronze sculpture of a Hindu goddess holds a lotus bud in her left hand. She wears a conical crown with mountain-like tiers (karandamukuta) and stands in a triple-bend pose (tribhanga). She wears a long garment that clings to her legs. This bronze probably represents one of the wives of the Hindu god Vishnu. Her body is defined by curving and diagonal forms and sinuous gestures suggestive of movement or even dance. In a South Indian temple, it would have been placed likely to the left of a bronze figure of Vishnu—her dynamic pose leading your eye toward her husband. (Keith McLeod Fund / Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Ganesha with His Consorts, early 11th century. Sandstone. Ganesha, the elephant-headed god of good fortune and auspicious beginnings, sits enthroned with his wives on his thighs. One wife may be Riddhi, “prosperity,” holding a lotus, and the other Siddhi, “accomplishment,” carrying a bowl of sweets. Below, the rat, Ganesha’s vahana (complement) nibbles at a sweet that has fallen from the bowl. This image was probably once part of the many carvings that covered the exterior of a Hindu temple. (John H. and Ernestine A. Payne Fund, Helen S. Coolidge Fund, Asiatic Curator's Fund, John Ware Willard Fund, and Marshall H. Gould Fund / Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Gong‑chime orchestra (gamelan lengkap), 1840 with later additions. Teak, bronze, and other materials. These instruments represent a

centuries-old tradition of collective music making that still thrives on the

Indonesian island of Java. Unlike a Western orchestra, a gamelan ensemble is

made and maintained as a set, unified by a consistent decorative concept and a

distinctive tuning character. Played by a group of about 20 performers, gamelan

music has a multilayered texture that ranges from quiet and haunting to loud

and stately. Olivier Messiaen’s Turangalîla-symphonie gets its name from an amalgamation of Sanskrit words; titles of movements allude to Hindu art and his use of percussion echoes the techniques and textures of the Balinese gamelan. The BSO performs Turangalîla-symphonie on its "Music for the Senses" program for April 11-14. (Museum purchase with funds donated by Mr. and Mrs. Bradford M. Endicott and Mr. and Mrs. Richard M. Fraser in honor of Jan and Suzanne Fontein, and the Frank B. Bemis Fund / Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Metallophone (gender barung),1840. Teak, bronze. A complete Javanese gamelan ensemble has six genders, three of which are lower-pitched (gender barung) and the other three higher pitched (gender panerus). Below each tuned bronze bar is a bamboo tube that helps the sound resonate. The gender performs a central role in gamelan music, and playing it requires great skill and coordination, as both hands move independently; the bars are struck with a padded mallet and dampened with the same hand. (Museum purchase with funds donated by Mr. and Mrs. Bradford M. Endicott and Mr. and Mrs. Richard M. Fraser in honor of Jan and Suzanne Fontein, and the Frank B. Bemis Fund / Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)