Symphony No. 5

Beethoven began sketching the Fifth Symphony in 1804 but returned to it only in 1807 after writing and revising his opera Leonore and completing his Fourth Symphony, Fourth Piano Concerto, Violin Concerto, the Razumovsky quartets, and other major works.

First performance: December 22, 1808, Theater an der Wien, Vienna, Beethoven conducting (in a concert also including, among other things, the premieres of the Pastoral Symphony and Choral Fantasy, and the first public performance of the Piano Concerto No. 4). First BSO performance: December 16/17, 1881, Georg Henschel conducting.

Beethoven grew up playing J.S. Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, and that prodigious collection had an indelible effect on his music. Among other things, the WTC may have implanted in Beethoven a sense of a synoptic body of work, meaning a collection of pieces in a single medium that seems to explore the full depth and breadth of what that medium can do, and beyond that the depth and breadth of what music itself can do. By the end of his life Beethoven had created three synoptic bodies of work: thirty-two piano sonatas, sixteen string quartets, and nine symphonies. In each of those streams of music stretching from his exploratory early phase to his transcendent final period, we find a steady renewal and growth, as if with each major work he set out to remake a medium and a genre.

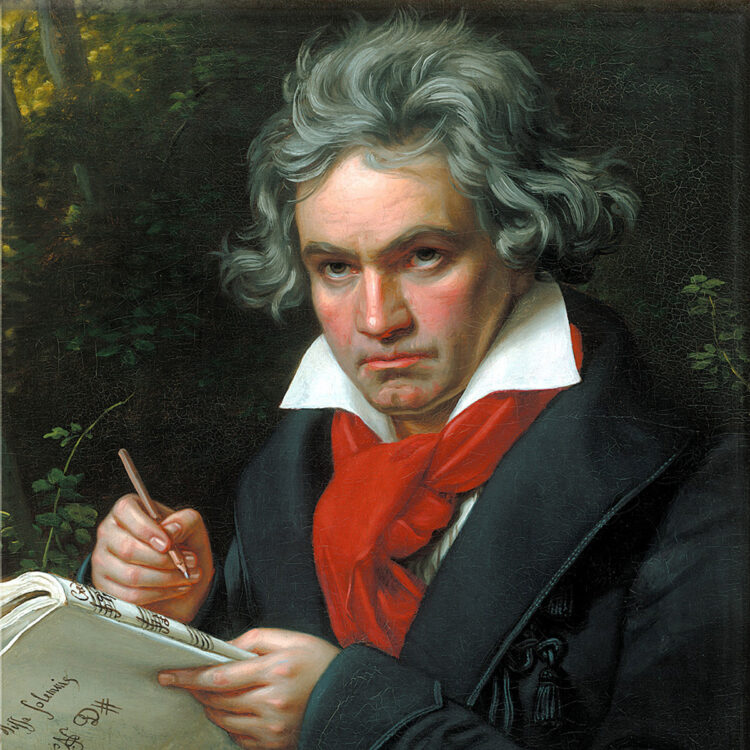

To the conception of a synoptic body of work Beethoven brought historic new elements. There was the sense of powerful personality. Where Haydn and Mozart even at their most poignant maintain a certain poise and Classical detachment, Beethoven seems to be grasping your lapel, speaking passionately to you person to person. In an age rocked by revolutions, it was inevitable that he would be called a revolutionary, yet he never called himself one. His music was a singular new voice, but one at the same time grounded in the legacy of Haydn, Mozart, Bach, and Handel. Call him not a revolutionary but a radical evolutionary.

All the same, his music was revolutionary in its impact. With the Eroica Symphony (No. 3) he expanded and intensified what Haydn had done in making the symphony the king of instrumental genres. Having absorbed his models, he systematically, synoptically, in every dimension, took his works further: longer, more intense, more contrasting in material, more grand and more intimate, more complex and more simple, from tragic to comic and prophetic to nostalgic. His symphonies stand as a collection of individuals unforgettable from the first time you meet them. Beyond that, they can be counted among history’s enduring testaments both humanistic and spiritual.

Beethoven wrote his Fourth Symphony near the end of the white-hot year of 1806, when, having recently finished a revision of Leonore and despite grueling illnesses he produced a collection of historic works including the Appassionata piano sonata, the Violin Concerto, and the three revolutionary Opus 59 Razumovsky string quartets. He wrote the Fourth Symphony quickly on a commission, and in it made a virtue of necessity with a radical simplification of form and content. Here Beethoven’s symphonic pattern becomes clear: odd-numbered symphonies heavier, even-numbered ones lighter, even as materials for both kinds of work appear nearly side-by-side in the composer’s sketchbooks.

The simplification of content and form of the Fourth Symphony carried over into the succeeding ones, each in its own way. In the Fifth, sketches for which appear as early as 1804, it is a matter of simplification plus intensification. The symphony begins with what became perhaps the most famous gesture in music, an explosive four-note tattoo that introduces a searing, force-of-nature first movement founded on that little motif implacably repeated. In this symphony there will be no stated narrative subject as in the Eroica, but still an implied journey from the fateful first movement to the triumphant finale. Beethoven is reported to have said of the opening tattoo: “Thus Fate knocks at the door!” Maybe he said that, maybe not, but there is no question that the first movement, with its relentless rhythmic figure, evokes something like fatality. And no question that the implied narrative from fatalism to triumph is full of significance for a musician to whom fate has dealt the worst of cards.

The double variations of the second movement are a lyrical respite from the stormy first, the beautiful main theme gently lilting, the lush second theme in the brass. The scherzo is the darkest and most ambiguous in all Beethoven’s symphonies, rising to a pealing, rather demonic horn theme, that contrasted by a robustly comic Trio. Finally a kind of fog descends, from which the joyous and exultant finale emerges in a blaze of brass. The exultant tone is sustained to the coda, except for a moment when the scherzo suddenly turns up again, injecting a touch of ambiguity. Beethoven knew that triumph is never complete. The demon can always come back.

From this climactic work of Beethoven’s Heroic Period his heroic voice would recede, most strikingly in the next symphony, the Pastoral.

Jan Swafford

Jan Swafford is a prizewinning composer and writer whose most recent book is Mozart: The Reign of Love. His other acclaimed books include Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, Johannes Brahms: A Biography, The Vintage Guide to Classical Music, and Language of the Spirit: An Introduction to Classical Music. He is an alumnus of the Tanglewood Music Center, where he studied composition.