Symphony No. 6 in F, Opus 68, Pastoral

Beethoven began sketching ideas for a symphony about a visit to the countryside as early as 1803, but did most of the work on the piece in late 1807-early 1808. The first performance took place December 22, 1808, in the famously overstuffed concert at Vienna’s Theater-an-der-Wien that also featured premieres of the Fifth Symphony, Fourth Piano Concerto, and the Choral Fantasy, among other things. The BSO first performed the piece in January 1882 under George Henschel, as part of the complete Beethoven symphony cycle in the orchestra’s first season. Serge Koussevitzky led the first Tanglewood performance during the first Tanglewood Festival concert on August 5, 1937, in a tent.

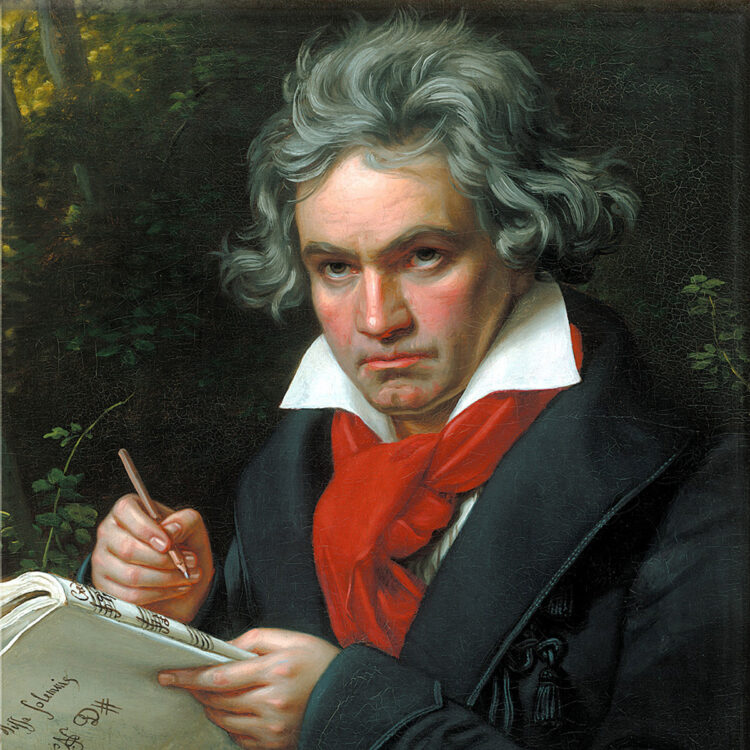

It is common that the circumstances of a work’s creation and the work itself take shape in antipathetic ways. So it was with Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, titled Pastoral. This work of placid and artless charm, mesmerizing as a midsummer day, involved the composer in as much labor and uncertainty as anything else he wrote. Its very conception led him on a protracted battle with himself. As is so often the case with artists, in the Pastoral, simple didn’t come easy.

Beethoven began the project determined to create a piece on the theme of a visit to the country, decked out with dancing peasants, babbling brook, and raging thunderstorm. At the same time, Beethoven rather deplored illustrative music, as did most cognoscenti of the time. The age saw many popular works depicting battles, shepherds, birds, baying hounds, and so on, and sophisticated listeners found them on the whole tacky. Even the descriptive moments in Haydn’s much-loved oratorios The Creation and The Seasons (including birds flying and singing, crickets chirping, a brook, a storm) attracted a good deal of critical disdain, in which Beethoven joined.

So why did Beethoven take up such a work fraught with potential for cliché and triviality, and why did he place the piece among his symphonies, which were the crown of his works? After all, he wrote plenty of potboilers including the gloriously trashy Battle Symphony. But he did not place such things among his real symphonies and did not give them the months of labor the Pastoral cost him—130 surviving pages of sketches, the most extensive that survive for any of his instrumental works.

With Beethoven the expressive and the technical always worked together, and in the Pastoral the technical challenge was daunting. When he came to the piece Beethoven had created a bold new scale of drama in the forms and genres he inherited from Haydn and Mozart. He filled sonata form and the other models with unprecedented intensity, individuality, contrast, even violence—as in the raging Fifth Symphony, written alongside the Pastoral and premiered on the same legendary 1808 concert. The game of the Pastoral is to turn the familiar forms in the opposite direction: an anti-violent, anti-contrast, anti-dramatic work. Is there any other symphony in which the first-movement sonata-form development section creates no tension whatever, but simply spins out calmly and beautifully, without surprises, without a minor key, virtually without a minor chord?

The Sixth Symphony is the anti-Fifth, answering the storms and ecstasies of the earlier work with a summer vacation in the country: no shadows, no drama except for a passing thunderstorm that gives way to a rosy sunset. Beethoven’s God was the primal creator of the Enlightenment, nature his scripture and cathedral. He shaped the Pastoral Symphony on the story of a country sojourn, but implicitly it is a sacred work.

First movement: “Awakening of happy feelings on arrival in the country.” It starts with a lilting tune unmistakably pastoral. A simple themelet chugs along unchanging like a donkey-cart for bar after bar. A later age would call this sort of music Minimalism. Themes like folktunes spin out effortlessly, the mood timeless, never departing from warm good cheer. No shadows, no griefs: bliss.

Second movement: “Scene by the Brook.” Where the first movement lilts, this one babbles and flows. Then “Merry Gathering of Peasants.” Late afternoon after the day’s work. This is the third-movement scherzo expected in a symphony. It begins cheerfully, its second theme introducing a parody of a village wind band where a drowsy bassoonist wakes up now and then to blat out a few notes. A driving, stamping peasant dance serves as the Trio. The repeat of the opening arrives as expected, but it is cut short by a distant rumble: “thunder bass,” Beethoven called it in a sketch. A moment of quiet, a smattering of rain, then with a crash a storm is on us: dissonant, roaring, harmonically ambiguous. This is not just a violent movement; it shatters the form itself.

The title of the fifth movement is “Joyful and Grateful Feelings After the Storm.” It is a partly hymnlike, partly folk-like song of thanks, most of it based on the distant alpenhorn call of the opening. Beethoven jotted in a sketchbook: “Arrival in the country. Effect on the soul.” For all its lovely tableaus, the Pastoral is as much interior monologue as illustration, a play of placid light and shade and storm across the souls of composer and listener.

JAN SWAFFORD

Jan Swafford is a prizewinning composer and writer whose most recent book, published in December 2020, is Mozart: The Reign of Love. His other acclaimed books include Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, Johannes Brahms: A Biography, The Vintage Guide to Classical Music, and Language of the Spirit: An Introduction to Classical Music. He is an alumnus of the Tanglewood Music Center, where he studied composition.