Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten

Quick Facts

- Composer’s life: Born September 11, 1935, in Paide, Estonia

- Year completed: 1977

- First performance: Estonian National Symphony Orchestra on April 7, 1977, in Tallinn

- First BSO performance: February 24, 2022, Andris Nelsons conducting

- Approximate duration: 8 minutes

Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten is scored for a single bell (on the pitch A) and string orchestra (first and second violins, violas, cellos, and double basses). The piece is about 8 minutes long.

Estonia gained its independence from Russia in 1920, while Russia was going through its own transition to become the central republic of the Soviet Union. Estonia maintained its sovereignty for just over twenty years but during World War II was caught between the USSR and encroaching Nazi Germany. Having liberated Estonia from Nazi occupation at the end of the war, the Soviet Union kept it and the rest of the Baltic States behind the Iron Curtain until the Soviet system collapsed; Estonia has been independent once again since August 1991. Estonia and its people represent a kind of cultural crossroads from Western Europe to Russia. The push-pull of political, religious, and cultural influences created clashes and blends of the Lutheran religion and intellectual traditions of Germany and Sweden with the Russian Orthodox Church, with Estonia’s distinct Finnic language and heritage as foundation.

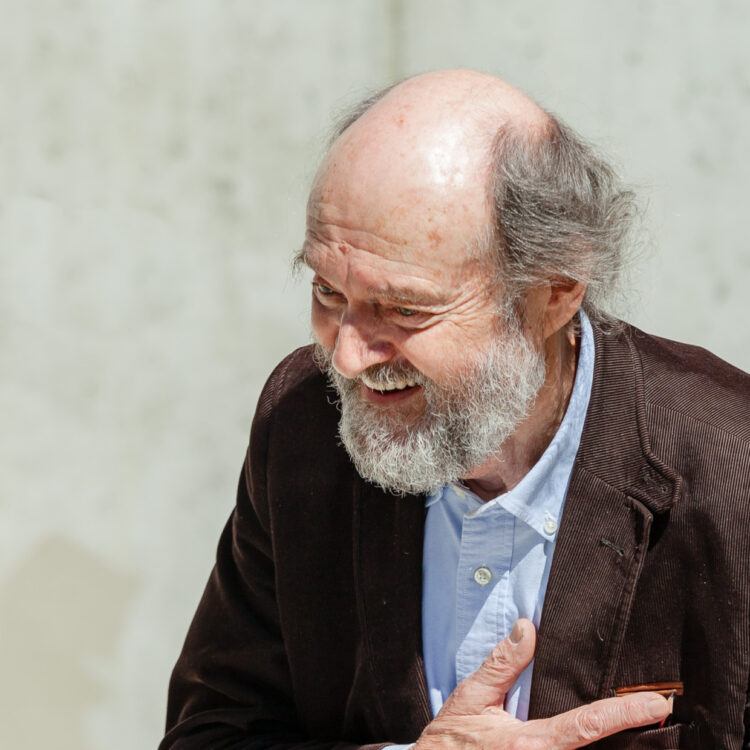

It was in this environment, a society intact beneath the Soviet Socialist influence of the latter half of the 20th century, that Arvo Pärt developed as an artist. As a child he attended a music school in addition to his regular education and began experimenting with creating his own music. He became quite a competent pianist and also played oboe and percussion. Pärt’s late teenage years coincided with the relaxation of Soviet policies for a time following Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953.

Pärt’s apprenticeship continued after high school at an intermediate music school, interrupted by his obligatory two-year military service. In 1957 he entered Tallinn Conservatory, where he studied Heino Eller, whom he holds as one of his most important influences. Concurrently he worked at Estonian Radio as a recording engineer and began composing for theater and film. By the time he graduated in 1963, he had established enviable professional credentials and a mastery of a range of compositional techniques.

During the late 1950s, composers gained greater access to music by progressive Western European and American composers working with serialism (carefully ordered series of pitch and other parameters, an expansion of Arnold Schoenberg’s 12-tone technique), chance processes, and other new ideas. More important than the specific techniques involved, however, was the very idea of freedom of artistic thought represented by the serious and breathlessly exuberant activity of the avant garde. It may surprise many admirers of Pärt’s most familiar work that he was probably the first Estonian to write a significant piece using the 12-tone method, his Necrology (1961), which was performed several times outside of Tallinn but received even greater attention as the object of public condemnation from Tikhon Khrennikov, the First Secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers.

Pärt’s use of serialism throughout the 1960s demonstrated his broader interest in formalism or process, prefiguring the stylized ritual of his later works. His Credo (1968) served as culmination of his first stylistic period. This watershed led to a crisis of aesthetic vision resulting in his adoption of what seem to be archaic compositional methods in the mid-1970s. Process, repetition, unequivocal gestures—the stuff of religious rites, particularly in the Orthodox churches where a vernacular Reformation never occurred—are the basis of much of Pärt’s work of the 1970s to the present. The conductor and singer Paul Hillier, who wrote an incisive study of Pärt’s music and has performed many of his pieces, drew a striking parallel between Pärt’s conceptual approach and the Russian Orthodox religious icon painting, which employs set of artistic formulae, a core visual language that recurs in the work of many different artists—a gilded crown, a type of costume, an arrangement of animals, even the shape of a face. Hillier relates the stylized lack of depth and perspective in icon painting to the timeless quality of Pärt’s music, achieved through repetition and eschewal of the “traditional,” that is, Western classical, passage of musical time.

Pärt’s return to the familiar triad and simplified tonality parallels the visual formulae of icon painting. Pärt supplemented his new ideas by extensive study of medieval and Renaissance music, which influence can clearly be heard in his later pieces. A specific sonic reference for the composer is the complex sound of bells, with their added significance as one of the public “voices” of the church. The repetitive patterns as well as the harmonic language of Pärt’s work since the early 1970s can be heard as abstractions of the bells’ sound and of the patterns of ringing changes on the bells for various church functions. Pärt calls the later pieces “tintinnabuli” (from the Latin for bell) works. The first of these were Modus (later revised as Sarah Was Ninety Years Old), Calix, and Für Alina, composed in 1976. Begun that same year, Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten was another of the pieces that defined Pärt’s new musical language. The composer wrote about his piece for the booklet of the album Tabula Rasa:

In the past years we have had many losses in the world of music to mourn. Why did the date of Benjamin Britten’s death—4 December 1976—touch such a chord in me? During this time I was obviously at the point where I could recognize the magnitude of such a loss. Inexplicable feelings of guilt, more than that even, arose in me. I had just discovered Britten for myself. Just before his death I began to appreciate the unusual purity of his music—I had had the impression of the same kind of purity in the ballads of Guillaume de Machaut. And besides, for a long time I had wanted to meet Britten personally—and now it would not come to that.

Pärt’s instinctive connection to Britten (1913-1976) might also relate to the older composer’s humanistic and artistic integrity, demonstrated most comprehensively in his War Requiem (1962), his pacifist masterpiece. Britten too, like Pärt, found in modern, avant garde music elements that he could bring into his own work without abandoning his individual musical vision.

Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten begins with a tolling bell on the pitch A that continues through the whole piece. The musical material is simple: a lamenting, descending A minor scale begun high in the violins and continued, overlapping in different tempos (each lower iteration half the speed of the previous), downward through the lower strings. The emotional affect of the piece has an impact that goes well beyond its straightforward and transparent architecture.

Robert Kirzinger

Composer and writer Robert Kirzinger is the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Director of Program Publications.