Fantasia in C minor for piano, chorus, and orchestra, Opus 80

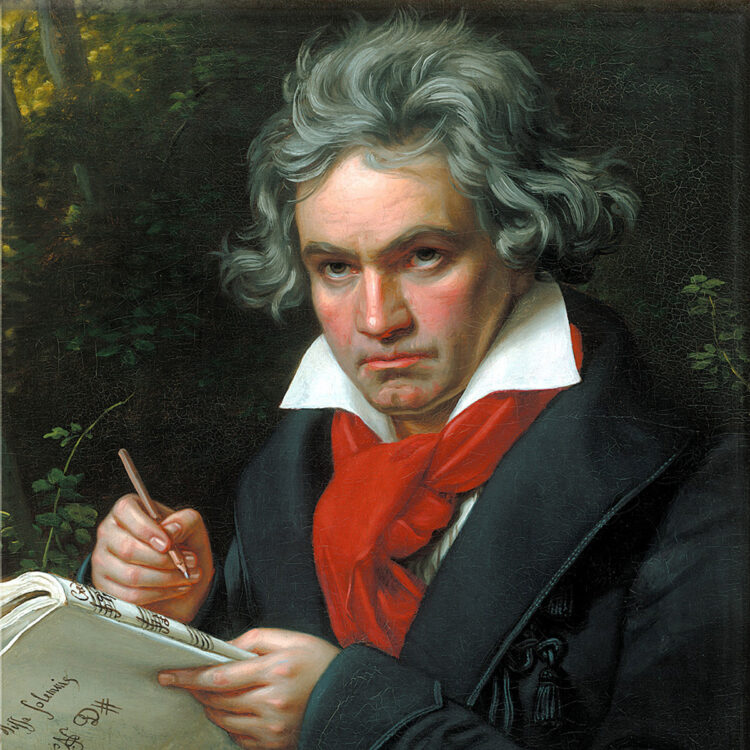

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn (then an independent electorate) probably on December 16, 1770 (he was baptized on the 17th), and died in Vienna on March 26, 1827. He composed the Choral Fantasy at the last possible moment to serve as grand finale for his own benefit concert of December 22, 1808, at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna. He himself was the pianist on that occasion.

In addition to the piano soloist, vocal soloists (two sopranos, alto, two tenors, and bass), and chorus, the score of the Choral Fantasy calls for an orchestra of flutes, oboes, clarinets, and bassoons in pairs, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings.

After having contributed both as composer and performer to a series of charity concerts in 1807 and 1808, Beethoven received permission to use the Theater an der Wien for a concert for his own benefit (i.e., one in which he would receive any profits that might accrue) on December 22, 1808. He chose this opportunity to reveal to the world some of his major new compositions in a program that consisted entirely of first performances of his music. Among the new works were such major pieces as the Fourth Piano Concerto (for which Beethoven himself was to be the soloist) and the Fifth and Sixth symphonies, as well as the concert aria “Ah! perfido” and several movements from the Mass in C, Opus 86 (which had to be advertised as “hymns in the church style” because the censor did not allow liturgical music to be performed in theaters). That list of pieces would seem to be enough to exhaust an audience (not to mention an orchestra), especially when all of the works included were utterly unfamiliar, difficult, and performed with far too little rehearsal.

But Beethoven decided that it wasn’t enough; he wanted a closing piece. He felt (with considerable justification) that it would not be fair to either the work or the audience to put the Fifth Symphony at the end of such a long program, even though it would make a rousing conclusion, because people would simply be too tired to pay much attention to it. So he put it at the beginning of the second half (the Pastoral Symphony opened the evening) and quickly composed a work designed specifically as a concert-closer, employing all of the forces that had been gathered for the concert (chorus, orchestra, and piano soloist), arranged in a variation form designed for maximum variety of color and for “easy listening.” He went back to a song, “Gegenliebe” (WoO 118), that he had composed more than a dozen years previously, ordered a new text written in a hurry by the obscure poet Christian Kuffner, and set to work.

The piece was finished too late for a careful rehearsal—which hardly mattered, since Beethoven and the orchestra, which was a “pick-up” group consisting of a heterogeneous mixture of professionals and reasonably advanced amateurs, had already had such a falling-out during rehearsals that the orchestra would not practice with Beethoven in the room, causing him to listen from an anteroom at the back of the theater and communicate his criticisms to the concertmaster. When the time came for the performance, just about everything went wrong: the concert was running to four hours in length, the hall was unheated and bitterly cold, the soprano had already ruined the aria out of nervousness. To top it all off, the Choral Fantasy fell apart during the performance (apparently through some mistake in counting in the orchestra) and Beethoven stopped the performance to begin it again. The financial outcome of the evening for Beethoven is unknown, but it certainly had a psychological effect on him: he never played the piano in public again.

The overall structure of the work is as bold as it is unusual: on the principle of gradually increasing the number of performers from minimum to maximum, Beethoven begins with an improvisatory introduction for solo piano, the finest example we have written down of what his own keyboard improvisations must have been like. The orchestral basses enter softly in a march rhythm, inaugurating introductory dialogue with the keyboard soloist hinting at the tune to come. Finally the pianist presents the melody that will be the basis for the remaining variations, and the finale is fully underway. One of the most striking things about the tune is the way it hovers around the third degree of the scale, moving away from it and then returning in smooth stepwise lines. Much the same description can be given of the main theme for the finale of the Ninth Symphony, for which reason the Choral Fantasy is sometimes viewed as a kind of dry run for the Ninth, though that mighty work, in which the choral finale is the powerful culmination of an enormous symphonic edifice, was still some fifteen years away. Still, the notion of variation treatment of a simple, almost hymn-like melody in the orchestra, followed by the unexpected appearance of voices, can be traced to this work. And though the Choral Fantasy does not pretend to such impressive architectural power as the finale of the Ninth, it certainly provided Beethoven with a closing number at once lively and colorful, naively cheerful, and original in form.