Concerto for Piano and Orchestra

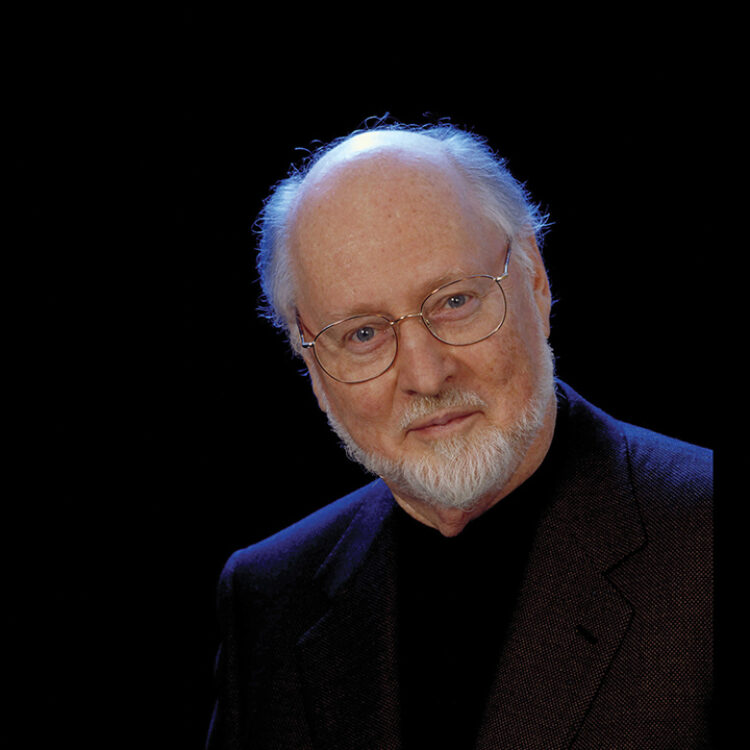

John Williams began his Concerto for Piano and Orchestra in 2022, composing it for pianist Emanuel Ax, who gives the world premiere performance Saturday, July 26, 2025, at Tanglewood under Andris Nelsons’ direction. Nelsons, Ax, and the BSO reprise the piece during the orchestra’s 2025-26 season at Symphony Hall in Boston.

As Boston Symphony Orchestra, Boston Pops, and Tanglewood audiences know well, throughout his career John Williams has composed concert music alongside his Hollywood activity. His early works in the concert sphere include a symphony in 1966 for André Previn (another musical polymath) and the Houston Symphony, and concertos for flute and for violin. He began writing concert music with much greater frequency after he was named Conductor of the Boston Pops in 1980 and came to know and work with principal players of that orchestra. He has written concertos for several members of the BSO/Pops, including former BSO tubist Chester Schmitz, oboist Keisuke Wakao, violist Cathy Basrak, and former principal harp Ann Hobson Pilot, as well as for members of other notable orchestras, such as Chicago Symphony former principal horn Dale Clevenger, New York Philharmonic principal bassoonist Judith LeClair, and Cleveland Orchestra principal trumpet Michael Sachs. He has also written works for soloist and orchestra for some of the most admired virtuosos in the world, including Yo-Yo Ma, Gil Shaham, and Anne-Sophie Mutter.

Like his new Concerto for Piano, many of Williams’s concert works have deep Tanglewood connections. Yo-Yo Ma premiered his Concerto for Cello with the BSO and Seiji Ozawa for the inaugural concert of Tanglewood’s Seiji Ozawa Hall in 1994 and his Highwood’s Ghost with Andris Nelsons, BSO Principal Harp Jessica Zhou, and the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra in 2018. Anne-Sophie Mutter premiered his Markings with the BSO and Andris Nelsons in 2017 and his Violin Concerto No. 2 under the composer’s direction in 2021. There have been other premieres here, as well, among them his song cycle Seven for Luck, on poems by Rita Dove; Just Down West Street—on the left, written for the Tanglewood Music Center’s 75th anniversary, and his solo piano work Phineas and Mumbett, premiered by Gloria Cheng during the 2012 Festival of Contemporary Music. Emanuel Ax, who made his Boston Symphony Orchestra debut at Tanglewood in August 1978, is a true Tanglewood denizen, having performed in more than 100 concerts here as orchestral soloist, chamber musician, or recitalist.

That John Williams is the most famous composer in the world, his film music familiar to billions, eclipses a bit the fact that he is a complete musician—a four-tool player, as it were, with skills as composer, arranger, conductor, and pianist. That last item was, in fact, first: Williams has been a pianist nearly all his life. Born in New York City, it was there he had his first piano lessons. After moving to Los Angeles with his family as a teenager and a stint in the Air Force, he returned to New York for his advanced musical training, studying with Rosina Lhévinne at Juilliard by day and playing in nightclubs by night. When he returned to Los Angeles, he established his career initially as a pianist in film studios, within a couple of years also taking on arranging and composing jobs. The stylistic variety mastered during those years laid the foundation for his celebrated ability to capture the musical essence of a film scene with a few evocative brushstrokes.

Williams refined that ability over the course of a decade with scores for television (Wagon Train, Land of the Giants) and film. He won his first Academy Award for his adaptation of the Fiddler on the Roof music for the big screen in 1972. His extraordinary 50-year partnership with Steven Spielberg began with The Sugarland Express (1974) and Williams won his first Oscar for Best Original Score for their second film together, Jaws, in 1976. His third and fourth Academy Awards for Best Original Score were also for Spielberg collaborations, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Schindler’s List. (He also won the Oscar for his score to George Lucas’s Star Wars.) Jazz, identifiable as such, has been relatively rare in his own film scores, the most notable exception being 2002’s Catch Me if You Can, in which Williams’s music mirrors the stylish 1960s depicted by Spielberg in the film. As a core part of his musical accent, jazz filters in and out of his film scores in variably explicit ways, but also appears more boldly in cameos—the most famous such instance being the cantina scene in Star Wars.

As Conductor of the Boston Pops from 1980 to 1993, Williams’s repertoire exhibited the sweep of his musical enthusiasms. Characteristic programs included his own and others’ film music, classical composers including Hector Berlioz, Camille Saint-Saëns, and Igor Stravinsky, “light” classical fare by Suppé and Johann Strauss, Jr., musical-theater composers including Leonard Bernstein, Kurt Weill, and Richard Rodgers, and performances by pop stars Johnny Mathis, Dionne Warwick, and Johnny Cash. And there was jazz: W.C. Handy, Fats Waller, Chuck Mangione, and collaborations with some of the genre’s greats: Tony Bennett, Mel Tormé with George Shearing, Oscar Peterson.

All this is to say that Williams is the sum of all these parts, and more: he continues to be inspired by the music and musicians he encounters, rechanneling those experiences into music that could be by no one else. His new concerto with its fourfold (including Emanuel Ax!) inspiration is a clear case in point. This is actually Williams’s second relatively recent work for piano and orchestra: he wrote a substantial Scherzo for Piano and Orchestra for Lang Lang in 2014, expanding it in 2021 by adding a prelude movement composed for Gloria Cheng. But this new piece is, as Maurice Ravel might have put it, a “proper concerto”—a work in the classical form of three movements, fast-slow-fast, familiar from the concertos of Mozart and Beethoven but also invoking the pianistic personalities, respectively, of Art Tatum, Bill Evans, and Oscar Peterson. Although there are no improvised passages, the solo part often provides space for flexibility of performance, for example in the cadenza-like opening of the first movement and markings of “dreamily” and “take time” to encourage the soloist toward a ruminating approach in the second. In this truly virtuoso concerto in which each movement has its challenges, the finale ratchets up the energy to another level, both for the soloist and the band.

The composer's own program note follows.

ROBERT KIRZINGER

Composer and writer Robert Kirzinger is the Boston Symphony Orchestra's Director of Program Publications.

John Williams on his Concerto for Piano and Orchestra

Composing a piano concerto was, for me, particularly challenging given the enormous canon of rich and diverse piano and orchestral masterworks created over the past centuries. Although my effort here is not a jazz piece per se, much of the impetus to write it down has been my memory of the particular “sound” produced by three legendary jazz pianists. Past this simple concept, the music is in no way an attempt to serve as a portrait of each of these artists, but merely to suggest and remember the unique artistic personalities of three men who greatly inspired me along with so many other lovers of the piano around the world.

Firstly, Art Tatum. When I was fifteen or sixteen years old, I remember a scene in a Los Angeles jazz club which welcomed underaged patrons providing they didn’t drink. I saw a large man who was clearly not sighted being carefully guided to his place at the piano. The lights were turned down so as not to offend his eyes. He seemed to be huge. His piano also seemed enormous…not with the usual 88 keys, but seemingly with twelve additional keys at either end of the keyboard, accommodating his massive reach. The size of his sound was awesome and reminded one of Rachmaninoff. He played three chords, listened, and played them again with an added note or two. He seemed satisfied and then began with a brief cadenza which served as his warm-up. The avalanche of gems that followed could hardly be imagined.

Secondly, Bill Evans. The second movement begins with a viola solo. Why? This may be because Bill was a quiet and very ethereal man who, when he approached the piano, always seemed to be less interested in playing than listening to what the piano may have to tell us. His piano eventually joins the viola, supporting Bill’s ethereal mood while further investigations ensue.

Thirdly, tall, handsome Oscar Peterson emerges, looking like an NFL wide receiver on his day off. After a brief salutation from the timpani, he begins with a bristling and famous “bebop” passage composed by whom we do not know but often attributed to Oscar and to the late Phineas Newborn, who also possessed a similar technical prowess. It serves as a reminder of Oscar’s athletic affinity, which he always displayed with taste and the most graceful control.

I’ve always so greatly admired pianist Emanuel Ax, who is universally celebrated for his technical brilliance, refined elegance and great artistic sensibilities. He is also one of the most gracious gentlemen I’ve had the privilege to know. When I first met Manny years ago, I asked him if in his travels he ever encountered a bad piano. He replied simply, “all pianos are my friends.” I had only mentioned to a few friends and associates that I might be interested in writing a work for piano and orchestra. You can imagine my surprise and delight when Manny called me to say, “if you write it, I will play it!” I could not have been more grateful and honored.

John Williams, June 2025