Leonore Overture No. 3

The first performances of Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3 were given in conjunction with performances of the revised, 2-act version of the opera Leonore at Theater-an-der-Wien, Vienna, in March 1806. The score of the overture calls for 2 each of flutes, oboes, clarinets, and bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, and strings (first and second violins, violas, cellos, and double basses). The overture is about 14 minutes long.

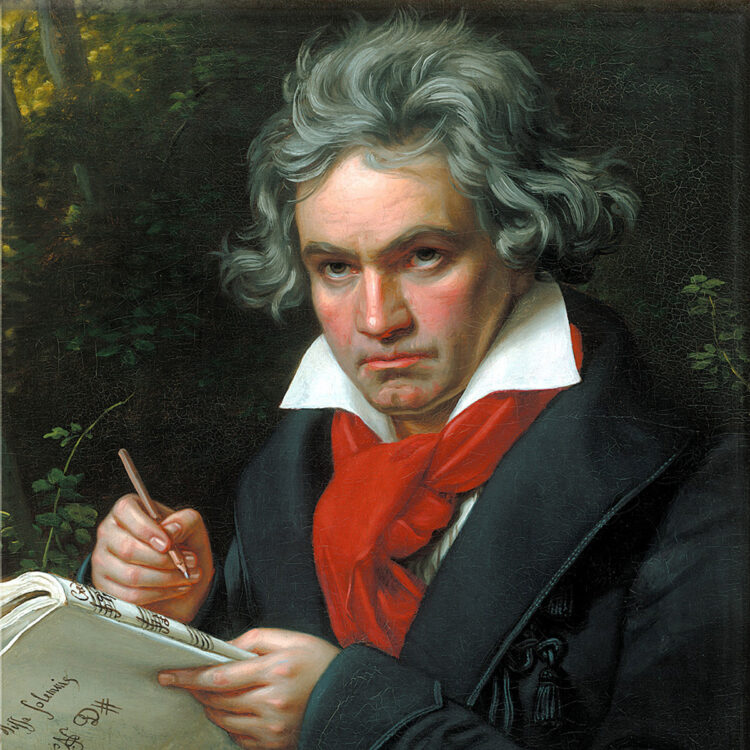

Beethoven’s love affair with opera was long and not fairly requited. During the last four years of his life, he cherished a plan to collaborate with the poet Franz Grillparzer on a work based on the legend of the fairy Melusine, and the success of the one opera he actually wrote, the work that began as Leonore and came finally to be called Fidelio, came slowly and late, and at the cost of immense pain. That Beethoven, over the course of a decade, wrote four overtures for the work tells its own story. These four works embody three distinct concepts, Leonore No. 2 (1805) and Leonore No. 3 (1806) being variant workings-out of the same design, while the Fidelio Overture (1814) is the most different of the bunch. The Fidelio Overture is the one that normally introduces performances of the opera, in accordance with Beethoven’s final decision on the question, and Leonore No. 3 is the most popular of the four as a concert piece. (Leonore No. 3 also shows up in the opera house from time to time, as a sort of aggressive intermezzo before the finale, but that is strictly a touch of conductorial vanity, and the fact that Mahler was among the first so to use the piece does not in any way improve the idea.) The Leonore Overture No. 1 represents something of a byway in Beethoven’s thoughts on how to introduce his opera; though it, like nos. 2 and 3, employs music from Florestan’s second-act aria, here this appears as a gentler contrasting central episode rather than in the slow introduction.

Leonore-Fidelio is a work of the type historians classify as a “rescue opera,” a genre distinctly popular in Beethoven’s day. A man called Florestan has been spirited away to prison by a right-wing politician by the name of Don Pizarro. Florestan’s whereabouts are not known, and his wife, Leonore, sets out to find him. To make her quest possible, she assumes male disguise and takes the name of “Fidelio.” She finds him. Meanwhile, Pizarro gets word of an impending inspection of the prison by a minister from the capital. The presence of the unjustly held Florestan is compromising to Pizarro, who determines simply to liquidate him. At the moment of crisis, Leonore reveals her identity and a trumpeter on the prison tower signals the sighting of the minister’s carriage.

Leonore Overtures 2 and 3 tell the story of Fidelio using somewhat varied approaches to their shared musical materials. Or each traces, at least, a path from darkly troubled beginnings to an anticipation of the aria in which Florestan, chained, starved, deprived of light, recalls the happy springtime of his life; from there to music of fiery energy and action, interrupted by the trumpet signal (heard, as it is in the opera, from offstage); and finally to a symphony of victory. It is, in a manner of speaking, Leonore No. 3 that is Beethoven’s ultimate distillation of Fidelio’s heroic-humanist ideal. It is too strong a piece and too big, even too dramatic in its own musical terms, effectively to introduce a stage action, but remains a potent and controlled musical embodiment of a noble passion.

Michael Steinberg/Marc Mandel

Michael Steinberg was program annotator of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1976 to 1979, and after that of the San Francisco Symphony and New York Philharmonic. Oxford University Press published three compilations of his program notes.

Marc Mandel joined the staff of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1978 and managed the BSO’s program book from 1979 until his retirement as Director of Program Publications in 2020.