Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Opus 37

- Composition and premiere: Sketches for Beethoven’s Concerto No. 3 appear as early as 1796 or 1797, but the principal work of composition came in the summer of 1800. Beethoven may have revised it in 1802 prior to the first performance, which took place in Vienna on April 5, 1803, with the composer as soloist. Sometime after completing the concerto—but before 1809—Beethoven wrote a cadenza for the Archduke Rudolph, though the concerto had been dedicated to Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia.

- First Tanglewood performance: August 7, 1960, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Pierre Monteux conducting, Leon Fleisher, piano.

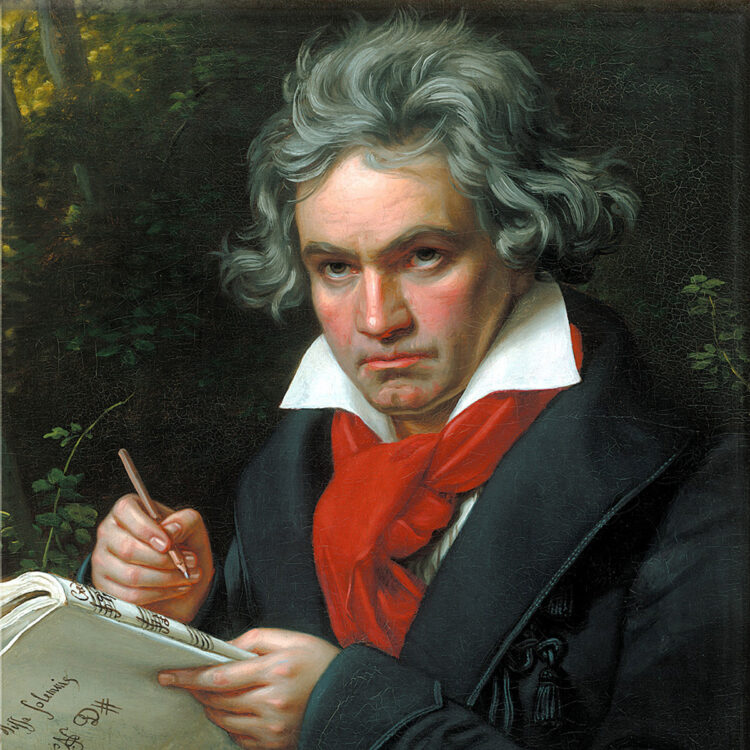

For virtuoso performer-composers like Beethoven, concertos were designed as personal showpieces. For that reason, the dynamic of performance and publication was different with concertos than with other genres. Beethoven would write a concerto, revising as he performed it, the cadenzas left for improvisation. Only when a concerto had been heard enough to become familiar to audiences did he publish it. Thus the deceptively late opus number for the Third Concerto, which was finished around late 1802 into 1803 but not published until 1804.

In fact, when the Third was premiered the solo part had not been written down at all, as a well-known story relates. Everybody nominally played from music in those days, so at the performance Beethoven carefully placed the solo part on the piano’s music stand. He was flanked by a young page-turner, who discovered that the pages were mostly blank, with only occasional “hieroglyphics” as reminders. The young man spent the performance anxiously watching Beethoven, waiting for his solemn nods to turn the empty pages. At a dinner afterward, Beethoven was roaring with laughter over the youth’s distress.

Even though much of the Third Concerto is audibly indebted to Mozart, in his handling of color and material Beethoven is playing sophisticated games of his own. The quiet unison opening in C minor recalls Mozart’s great C minor concerto, K.491, of which Beethoven once said—after hearing a performance in Vienna’s Augarten in summer 1799—“[I’ll] never do anything like that!” Still, even in relatively backward-looking works like this one, Beethoven possesses a mature mastery of form and conception. Like many pieces of the “First Period,” the Third Concerto is more than beautiful; it is a remarkable essay in musical form and logic.

The beginning sets a tone dark and dramatic, with a certain military-march aspect familiar in concertos by Beethoven and many others. This, his only minor-key concerto, does not really have the driving and demonic tone of the Fifth Symphony’s first movement and other examples of his “C minor mood”; neither is this concerto the full-blown “heroic” style of the Middle Period. As such, it has a distinctive voice in Beethoven’s orchestral music.

The entire concerto will turn around a few ideas from the beginning. The first measure is a rising figure, the second measure a down-striding scale, the third measure a martial drumbeat. Separately and together, these ideas will pervade the first movement and beyond. The most important, as it turns out, is not one of the melodic motifs but rather the drumbeat rhythm. The opening string phrase is echoed a step higher by the winds, who add another fundamental idea: a line that rises up to a piercing dissonance on A-flat. In various guises, that dissonant A-flat will resonate throughout the piece and find its resolution only at the end.

The second theme of the opening movement is, as expected, a lyrical contrast to the sternly militant opening, and brings us to the piano’s entrance on an explosive upward-rushing scale. The soloist takes up the main theme, establishing a commanding personality in the dialogue with the orchestra.

Much of the music from the solo entrance on, especially the middle development section, is dominated by the drumbeat figure in constantly new forms—but never, so far, played by an actual drum. After the piano’s concluding cadenza, however, the rhythmic motif finally turns up in the timpani, as if emerging as a “real” drumbeat, in a duet with the piano. That moment of piano and timpani together appears to be the first idea Beethoven jotted down for the concerto, in 1796: “For the Concerto in C minor, kettledrum at the cadenza.” Here was the generating conception from which the work developed.

The second movement is in a striking E major, about as far from C minor as a key can be. But the first note in its solemnly beautiful opening theme is G-sharp, the same pitch as A-flat. The starring pitch continues to resonate. The form is a simple ABA, the piano now with an air of rapturous improvisation. The final chord of the second movement places G-sharp on the top in strings. The piano picks up that note and turns it back into A-flat to begin what will be a lively and playful rondo, despite the C minor tonality. The middle section is in A-flat major—the starring note now with its own key. As a kind of musical joke, Beethoven turns the A-flat back into G-sharp and on that pivot shoves us for a moment into E major, the key of the slow movement. After a mini-cadenza for the piano the 2/4 main theme is transformed into a Presto 6/8, driving to the end in pealing C major high spirits.

JAN SWAFFORD

Jan Swafford is a prizewinning composer and writer whose most recent book, published in December 2020, is Mozart: The Reign of Love. His other acclaimed books include Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, Johannes Brahms: A Biography, The Vintage Guide to Classical Music, and Language of the Spirit: An Introduction to Classical Music. He is an alumnus of the Tanglewood Music Center, where he studied composition.