Violin Concerto

Quick Facts

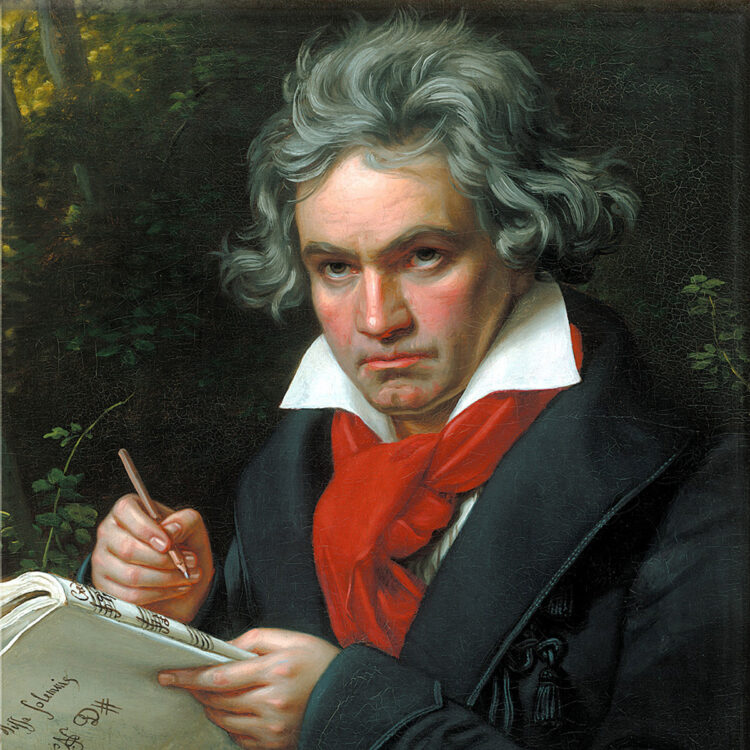

- Composer’s life: Baptized December 17, 1770, in Bonn, Germany; died March 26, 1827, in Vienna, Austria

- Year completed: 1806

- First performance: December 23, 1806, Theater an der Wien, Vienna, with Franz Clement as soloist

- First BSO performance: January 4, 1884, Georg Henschel conducting, with Louis Schmidt, Jr., as soloist

- Approximate duration: 47 minutes

Ludwig van Beethoven was baptized in Bonn, Germany, on December 17, 1770, and died in Vienna on March 26, 1827. He completed the Violin Concerto in 1806, shortly before its first performance on December 23 that year with soloist Franz Clement at the Theater an der Wien in Vienna.

In addition to the solo violinist, the score of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto calls for an orchestra of one flute, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani, and strings.

The works Beethoven finished in the last half of 1806—the Violin Concerto, the Fourth Symphony, and the Fourth Piano Concerto among them—were completed rather rapidly by the composer following his extended struggle with the original version of his opera Fidelio, which had occupied him from the end of 1804 until April 1806. The most important orchestral work Beethoven had previously completed was the Eroica, in which he overwhelmed his audiences with a forceful new musical language reflecting both his own inner struggles in the face of impending deafness and also his awareness of the political atmosphere around him. The next big orchestral work to embody this “heroic” style would be the Fifth Symphony, which began to germinate in 1804 but was completed only in 1808. Meanwhile, a more relaxed sort of expression began to emerge, incorporating a heightened sense of repose, a more broadly lyric element, and a more spacious approach to musical architecture. But while they share these characteristics, it is important to remember that the Violin Concerto, Fourth Symphony, and Fourth Piano Concerto do not represent a unilateral change of direction in Beethoven’s approach to music; rather they reflect the emergence of a particular element that appeared strikingly at this time. Sketches for the Violin Concerto and the Fifth Symphony in fact occur side by side; and that the two aspects—lyric and heroic—of Beethoven’s musical expression are not entirely separable is evident also in the fact that ideas for both the Fifth and Pastoral symphonies appear in the so-called Eroica sketchbook of 1803-04, and that these two very different symphonies—the one strongly assertive, the other more gentle and subdued—were not completed until 1808, two years after the Violin Concerto.

The prevailing lyricism and restraint of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto doubtless also reflect the particular abilities of Franz Clement, the violinist for whom it was written. More than just a virtuoso violinist, Clement was also an accomplished pianist, score-reader, and accompanist; from 1802 until 1811 he was conductor and concertmaster of Vienna’s Theater an der Wien. Beethoven headed the autograph manuscript with the dedication, “Concerto par Clemenza pour Clement, primo Violino e direttore al Teatro a vienna dal L.v. Bthvn 1806.” It seems that Beethoven completed the concerto barely in time for the premiere at the Theater an der Wien on December 23, 1806. Clement reportedly performed the solo part at sight, but this did not prevent the undauntable violinist from interpolating, between the two halves of the concerto, a piece of his own played with his instrument held upside down—or at least so it was said, for many years. Only later, however, did the concerto come to win its place in the repertory, after the 13-year-old violin virtuoso Joseph Joachim played it in London on May 27, 1844, with Felix Mendelssohn conducting. (Joachim left a set of cadenzas for the concerto that are sometimes still heard today, as did another famous interpreter, Fritz Kreisler).

By all reports, Clement’s technical skill was extraordinary and his intonation no less than perfect, but he was most highly regarded for his “gracefulness and tenderness of expression,” for the “indescribable delicacy, neatness, and elegance” of his playing, attributes certainly called for in this concerto. But this is not to say that Beethoven’s concerto is lacking in the virtuoso element, something we may claim to hear more readily in, say, the later 19th-century violin concertos by Brahms and Tchaikovsky, both of which have more virtuosity written into the notes on the page, and which may seem bigger or grander simply because of their more romantically extrovert musical language. In fact, an inferior violinist will get by less readily in the Beethoven concerto than in any of the later ones: the most significant demand this piece places upon the performer is the need for utmost musicality of expression, virtuosity of a special, absolutely crucial sort.

An appreciation of the first movement’s length, flow, and musical argument is tied to an awareness of the individual thematic materials. It begins with one of the most novel strokes in all of music: four isolated quarter-notes on the drum usher in the opening theme, the first phrase sounding dolce in the winds and offering as much melody in the space of eight measures as one might wish. The length of the movement grows from its duality of character: on the one hand we have those rhythmic drumbeats, which provide a sense of pulse and of an occasionally martial atmosphere, on the other the tuneful, melodic flow of the thematic ideas, against which the drumbeat figure can stand in dark relief.

The slow movement, in which the flute and trumpets are silent, is a contemplative set of variations on an almost motionless theme first stated by muted strings. The solo violinist adds tender commentary in the first variation (the theme beginning in the horns, then taken by the clarinet), and then in the second, with the theme entrusted to solo bassoon. Now the strings have a restatement, with punctuation from the winds, and then the soloist reenters to reflect upon and reinterpret what has been heard, the solo violin’s full- and upper-registral tone sounding brightly over the orchestral string accompaniment. Yet another variation is shared by soloist and plucked strings, but when the horns suggest still another beginning, the strings, now unmuted and forte, refute the notion. The soloist responds with a trill and improvises a bridge into the closing rondo.

By way of contrast, the music of this finale is mainly down-to-earth and humorous; among its happy touches are the outdoorsy fanfares that connect the two main themes and, just before the return of these fanfares later in the movement, the only pizzicato notes asked of the soloist in the course of the entire concerto. These fanfares also serve energetically to introduce a cadenza, after which another extended trill brings in a quiet restatement of the rondo theme in an extraordinarily distant key (A-flat) and then the brilliant and boisterous final pages, the solo violinist keeping pace with the orchestra to the very end.

Marc Mandel

Marc Mandel joined the staff of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1978 and managed the BSO’s program book from 1979 until his retirement as Director of Program Publications in 2020.