Violin Concerto No. 2

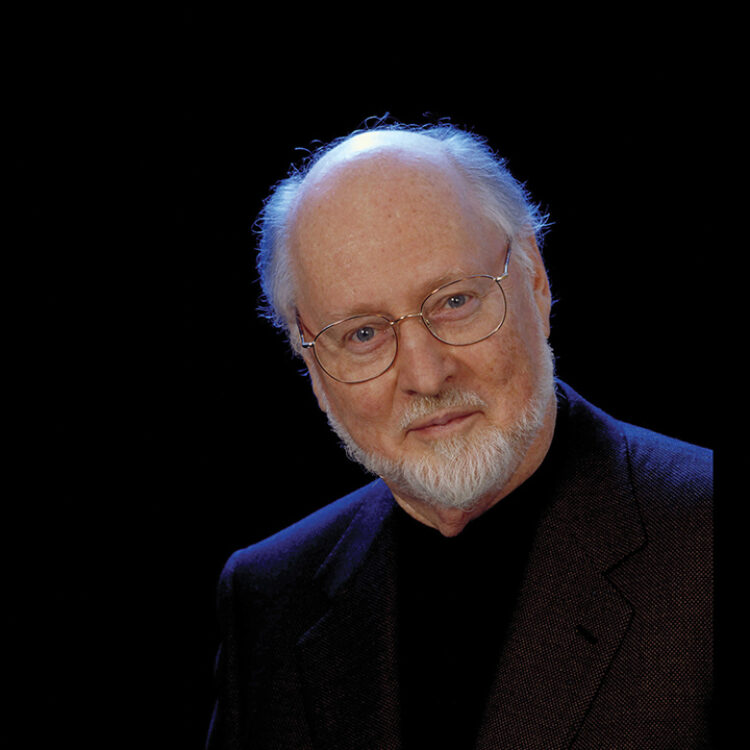

John Towner Williams was born February 8, 1932, in New York City, and lives in Los Angeles, California. He wrote his Violin Concerto No. 2 for violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, who gave the world premiere performance at Tanglewood on July 24, 2021, with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by the composer.

The score of the Violin Concerto No. 2 calls for 3 flutes (3rd doubling alto flute and piccolo), 3 oboes (3rd doubling English horn), 3 clarinets (3rd doubling bass clarinet), and 3 bassoons (3rd doubling contrabassoon); 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, and tuba; timpani, percussion (glockenspiel, xylophone, vibraphone, marimba, chimes, large and small triangles, high and medium sizzle cymbals, bright cymbal, 4 suspended cymbals, choke cymbal, 3 tam-tams, high slapsticks, 2 tambourines, small ratchet, Japanese woodblocks, tuned drums, bass drum, taiko), harp, piano and celesta, and strings (violins I and II, violas, cellos, double basses). The concerto is about 34 minutes long.

John Williams’s Violin Concerto No. 2 is the result of many years of collaboration and friendship between John Williams and Anne-Sophie Mutter. At Tanglewood in summer 2017, the violinist had given the world premiere performance with the Boston Symphony Orchestra of a new work requested by and written for her, John Williams’s Markings for violin and orchestra. The violinist, one of the preeminent soloists in the world, was well aware of the composer’s deep love for the violin, not only from his concert works for violin and orchestra—the Violin Concerto and TreeSong—but also the beautiful Three Pieces from Schindler’s List, derived from his Academy Award-winning film score. His new Violin Concerto No. 2 is a serious and substantial addition to a tradition that encompasses some three hundred years of repertoire, from Vivaldi through Mendelssohn, Tchaikovsky through Berg, to Sofia Gubaidulina and André Previn. In requesting a new concerto from John Williams, Ms. Mutter expands her already remarkable, stylistically varied string of commissions from such composers as Witold Lutosławski, Wolfgang Rihm, Krzysztof Penderecki, Henri Dutilleux, and Sebastian Currier, among others.

Already very active in the 1960s in both TV and film, Williams’s work had become familiar to viewers with his scores for TV series (Lost in Space and Wagon Train, among many others), TV movies of Jane Eyre and Heidi, and such feature films as How to Steal a Million, Goodbye, Mr. Chips, The Cowboys, and The Poseidon Adventure. It was his music for Jaws (1975) that upped the ante; two years later, Star Wars cemented his status as a household name and as one of the most famous American composers in history. Jaws was only the second in a string of collaborations with Steven Spielberg; it was followed by twenty-six further films, including E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Schindler’s List, the Indiana Jones and Jurassic Park series, The BFG, and many others. The composer has also worked with such prominent directors as Oliver Stone, Chris Columbus, and of course George Lucas in the Star Wars franchise. The winner of five Academy Awards, Williams trails only Walt Disney as the Academy’s most-nominated individual, with fifty-two total Oscar nominations. He has also won numerous Grammy, Golden Globe, and Emmy awards, among many other honors.

The overwhelming popularity and familiarity of John Williams’s film music and his status as a Hollywood icon have tended to overshadow an impressive catalog of works for the concert stage. The bulk of that catalog dates from about the beginning of his tenure as Conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra. The circumstances surrounding many, if not most, of these pieces is completely in keeping with the generosity of spirit and joy in connections with others that are such a well-known aspect of Williams’s personality. Many of these pieces are concertos written with specific soloists in mind—especially members of the Boston Pops with whom he worked during his tenure as the titled conductor of the orchestra and in the decades following. These include a tuba concerto for former BSO member Chester Schmitz; a concerto for BSO oboist Keisuke Wakao, and a viola concerto for Pops principal viola Cathy Basrak, all premiered by the Pops under the composer’s direction.

Williams’s harp concerto, On Willows and Birches, was a gift for former BSO principal harp Ann Hobson Pilot at the time of her retirement from the orchestra. As the result of a casual suggestion by BSO violist Michael Zaretsky, Williams wrote one of his rare chamber-music scores, Duo concertante for violin and viola, for Zaretsky and BSO violinist Victor Romanul. He also wrote a tribute to Seiji Ozawa to mark the conductor’s historic tenure as the BSO’s music director.

One of William’s earliest concert works, predating his time with the Boston Pops, is a violin concerto—which we should perhaps now designate No. 1—that he wrote in part as a reaction to the death of his wife of eighteen years, the actress Barbara Ruick. Begun in 1974, completed by 1976, and slightly revised in the late 1990s, that concerto was premiered in Saint Louis in 1981 but has found its highest-profile champion in violinist Gil Shaham, who recorded the piece with the Boston Symphony Orchestra under the composer’s direction. Now at a distance of nearly a half-century, Williams brings decades more emotional weight and artistic life to bear in composing this lyrical and personal new work for Anne-Sophie Mutter. The composer’s thoughtful and poetic comments on his new piece are on page 32.

Robert Kirzinger

Composer and writer Robert Kirzinger is the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Director of Program Publications.

John Williams on his Violin Concerto No. 2

Composing program notes has always been challenging for me. These descriptions always seem to try to answer the question “what is this music about?” And while music has many purposes and functions, I’ve always believed that in the end, the music ought to be free to be interpreted through the prism of every listener’s own personal history, prior exposures and cultural background. One man’s sunken cathedral might be another woman’s mist at the dawning. The meaning must therefore reside, if you’ll forgive me, in the “ear of the beholder.”

I can only think of this piece as being about Anne-Sophie Mutter, and the violin itself—an instrument that is the unsurpassed product of the luthier’s art. With so much great music already written for the instrument, much of it recently for Anne-Sophie herself, I wondered what further contribution I could possibly make. But I took my inspiration and energy directly from this great artist herself. We’d recently collaborated on an album of film music for which she recorded the theme from the film Cinderella Liberty, demonstrating a surprising and remarkable feeling for jazz. So, after a short introduction, I opened the Prologue of this concerto with a quasi-improvisation, suggesting her very evident affinity for this idiom. There is also much faster music in this movement, which while writing, I recalled her flair for an infectious rhythmic swagger that is particularly her own.

In the beginning of the next section or movement, a quiet murmur is created by a gentle motion that I think of as being circular, hence the subtitle Rounds. At one point you will hear harmonies reminiscent of Debussy, but I ask you to reflect on another Claude… in this case Thornhill, a very early hero of mine who, it can be justly said, was the musical godfather of the Gil Evans/Miles Davis collaboration. It is also in this movement that a leitmotif or theme appears, later restated in the Epilogue.

Dactyls, a borrowed word from the Greeks, which we use to describe a three-syllable effect in poetry, as well as the digit with its three bones, may serve to describe the next movement. It is our third movement, in a three meter, and features a short cadenza for violin, harp, and timpani… yet another triad. The violin provides an aggressive virtuosity that produces a rough, waltz-like energy that is both bawdy and impertinent.

The final movement is approached “attacca” by the violin and harp, where the two instruments reverse their relative balances in a kind of “sound dissolve.” In this way, they transport us to the Epilogue. It is in this final movement that the motif introduced in Rounds returns in the form of a duet for violin and harp, closing the piece with a gentle resolution in A major that might suggest both healing and renewal.

John Williams, June 28, 2021